“Say it out loud”. I spent quite a while, swimming in drink, tied to the house like a wheel on which I was slowly being broken.

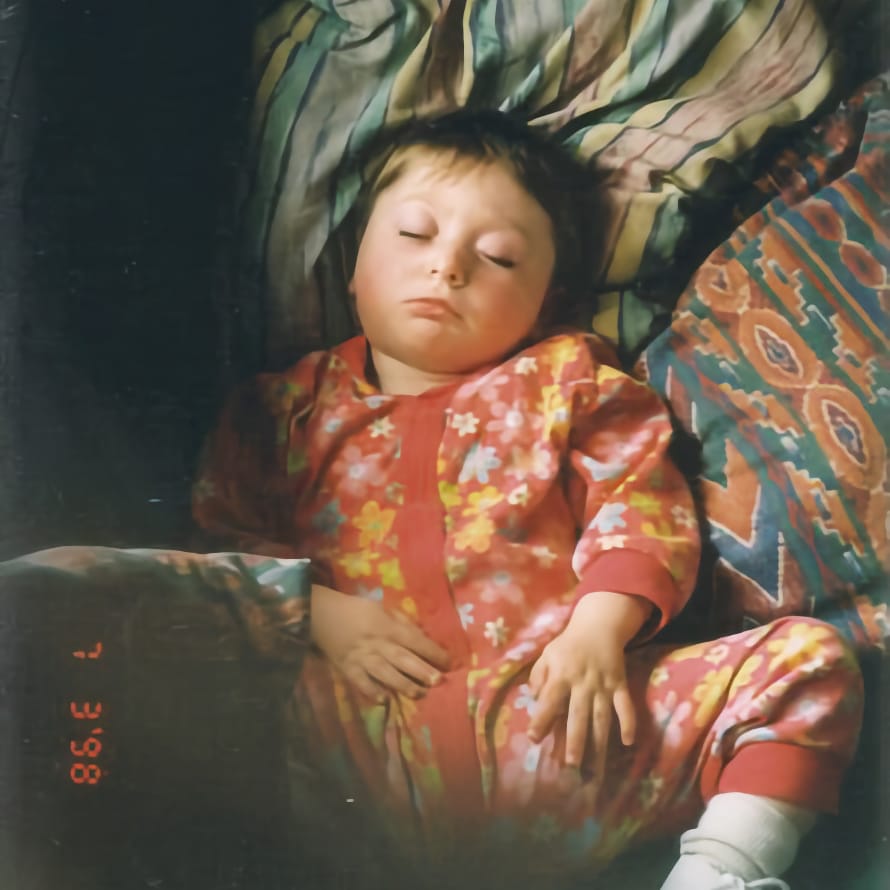

Writing fiction means drawing on your life from time to time. I’d been writing a short story about a mortician. I took a break and I was back at that the now closed morgue and coroner’s court in Glebe in Sydney. It two weeks after the death at home of my nine-year old daughter, Zuzu. It was July, the winter sky outside was deep blue. I was looking at Zuzu’s little body, which was laid out behind glass like a museum exhibit.

The top of the post-mortem Y-scar was visible starkly splitting her body from her stomach button to neck. Zu’ had been dead for two weeks. Her skin was waxy but her hair had grown a little and I wanted to brush it. I finally remembered the green, short-sleeved dress and the smart, shiny black shoes I’d bought to the morgue for Zuzu as part of the change of clothes for her cremation. She rarely wore smart, shiny shoes due to her cerebral palsy. The morgue assistant looked at the bag hanging from my right hand and offered to take it from me.

“Can I brush her hair?” I asked the lady who was in charge of everything in the world at the moment.

“Do you really want to? She won’t feel the same. It might hurt your memory.” I was taken by the phrase. I wanted to pick Zu’ up and brush her hair, which I’d cut in previous years into a bob. I wanted to hug her. But I understood what I was being told.

I had picked Zuzu up when I’d found her dead in her bed that morning a week previously. She wasn’t quite cold then. I’m not going to write more about that picture, at least not now, there is no point in recreating that image. Nothing useful can come from reinhabiting that place. I’ve still not created a stabilised, decent image to convey those details yet. I doubt I ever will.

Back in the morgue, the assistant asked again, “Are you sure?

I was sure, I did want to tidy Zuzu’s hair just a bit. Just one final element of a relationship of father to daughter. Just one last touch.

“Yes, thank you, I am”, no faltering, there was such little energy left in me.

After a few moments Zuzu’s body was returned to the world outside the glass. I had her hairbrush in my hand, it weighed so much that I could hardly lift it to brush her fine, beautiful hair.

I kissed her forehead, gently. She smelled of the morgue and post-mortem table, distance, anything but here, but of my desolation and fear. I was scared of my daughter’s corpse because although it obviously was her, large blue eyes, her resting face was peaceful as usual, her hands clenched as her cerebral palsy forced them to be even in her relaxed moments.

For a fleeting moment, as I lifted my face from her forehead and the kiss I’d left there as I did every night, for that moment I caught her smell, at least I hope so.

I was crying from my gut, the lady passed me a small, sanitised paper towel to wipe my eyes and cheeks. I took a moment to look around the room. Surprisingly now I only have a faint, washy, hallucinogenic view of that room, probably wrong.

It was bright, high contrast, white light unlike the bright, chilly, damp winter light from outside. At least behind me it was. Looking at where Zuzu had been laid out, it was darker.

The assistant took the wipe from my hand and, to this day I remember what she said with great and beautiful clarity. She said to me, “Don’t worry, there’s somebody here at all times. She won’t be alone. And we never turn the lights out, so she won’t be in the dark.”

At first, I had no idea why she was saying this but it made me feel slightly better. “I am so sorry”, I wanted her to touch my hand just for human contact, she didn’t of course. She continued, “I will take care of your Zuzu. I will make sure she’s ok.” She emphasised the word, “will”. I believed her. I left the morgue, and sat in my car. Zuzu’s wheelchair was still in the back and my next task was to work out what to do with it. But first, it was time to drive Zuzu’s memory to the Domain in Sydney, down to Mrs Macquarie’s chair where we used to sit and look out into the world.

That morgue assistant had a terrible, horrible job to do. I can’t imagine how she felt when she got home that night. A man, sobbing and shaking and trying to brush his little dead girl’s hair. A man staring into the distance in pieces, and this public servant dragged up from the depths of her experience, soul and good heart some beautiful, supporting and decent words.

I still remember them. They still help even when memories burst in of the morgue itself.

Thank you for your service.

The other point of this post is to “Say it out loud”. I spent quite a while, swimming in drink, tied to the house like a wheel on which I was slowly being broken. Scared to go out because other people and their daughters would be there.

I realised that dealing face on with the morgue and Zuzu’s hair, the Y-scar and the cold would never go away. So, I’d better deal with them if I wasn’t going to let my daughter die again and again and again in my heart and mind.

So, here we go. When it hurts, I write.