Chapter 1

In which our hero’s history catches up with him. We discover his family. The mob solidifies and a lady of ability is introduced.

Revolving doors on the 41-storey building. It has revolving doors and this, of course, was a problem for John McDonald-Sayer. He had stipulated when best laying plans that nothing to do with Barleycorn Buildings should revolve.

“If I’d wanted revolutions, I would have hired a Cuban,” he had joked, weakly.

“Yes, sir”, replied the worried architect.

Not only are the doors revolving, the top of the building is too. Even more annoyingly so are all eight of the elevators that crawl up and down the sides of the tower like beads of water on a turning pole dancer.

McDonald-Sayer turns away from his broken dream statement of self. The final indignity grazes his rapidly tearing up vision: “Barely Conned Bluidings” declares the back of the 10-metre high sign. The front of the sign is still covered in tarpaulin waiting to be uncovered by Jack Nicholson or Keanu Reeves or Aung San Suu Kyi (depending on commitments) at the cock’s call on Grand Opening Day.

“Someone”, ponders McDonald-Sayer,“is taking the piss”.

He is correct but it must be said that it is mostly his fault. The bit that isn’t relates to several million dollars of national lottery winnings that now sits mainly in the bank account of the not really that worried architect. His lucky number had come up shortly before McDonald-Sayer left for a mind expansion trip to South America. He had chosen it based on the telephone number of the gun seller from whom he was going to purchase the gun with which he intended to shoot his master and tormentor down in cold, cold blood.

McDonald-Sayer is not aware of this. Such is the mighty power of knowledge.

“Will it change your life?” asked the architect’s deeply predictable girlfriend who had stuck by him through his studies and early career.

“Too bloody right it will – but not as much as it’s going to change someone else’s.”

McDonald-Sayer has never related well to other human beings because he has never needed to, such is the power of money. He’d always been cushioned by several billions of dollars. These had been earned via several hundred dodgy deals, street brawls, arsons, insurance frauds, possibly a murder or five and some excellent legal advice over the preceding centuries. What McDonald-Sayer saw as good humoured banter and ribbing, others saw as arrogant bullying and fear inducing overbearing power plays. He is not aware of this reaction in other people. Such is the power of self-knowledge.

So, the architect; in fact, the entire team down to the tea ladies who supplied the brickies with tea and thrills, hate his guts. After some judicious sharing of the architect’s lottery money, they’d all agreed that as McDonald-Sayer was flat on his back Peru or Columbia they would not leave the job. Not until it was finished and quite completely fucked-up.

They proceeded with the kind of vigour and dedication that drew pages of appreciation in related journals and even gasps of awe from passers-by. They finished the project ahead of schedule and massively over budget with no interference from any of McDonald-Sayer’s advisors – who, like them, hated their gunner and had been pleased to jumped ship wrapped in financial lifejackets supplied by the mutinous crew.

McDonald-Sayer, leaves the site, possibly forever, and motors his Roller Roycer out to the countryside where he stamps it to a stop on the thickly gravelled drive of the family seat. It skids, it scars, the car hates McDonald-Sayer. His mother, flanked by Cadrew the butler, stands at the open door smiling the smile of a woman who never sees the dark side of anything anywhere ever because she has never actually seen the dark side of anything, anywhere, ever. Cadrew has no expression – the muscles of his face having been cast into the neutral shortly after his sixth birthday at the expense of the McDonald-Sayers.

John remains in the car, slamming the steering wheel with his fists, tears sparkling from his face; screaming a Buddhist chant of serenity.

“My little darling is such an expressive spirit, Cadrew, I am often amazed that he never chose theatrical production as a career,” Mrs McDonald-Sayer’s fairy-floss voice wafts past the butler who, nodding, steps forward and opens the driver’s door.

McDonald-Sayer falls out of the car, foetal onto the path and yells – serene in his petulance – at Cadrew.

Soundless, sprightly and showing some of his years, the butler moves at a hover to the boot of the motor and collects the luggage.

Mrs McDonald-Sayer calls wanly, “Darling boy, tea is waiting, we have scones and Mrs Cadrew’s homemade strawberry jam. Your father is coming up from the country to meet you. Maybe you two can smoke a cigar and play at billiards?”

She reverses into the foyer, smile affixed, tidies a floral arrangement and steps aboard the magnetically propelled platform to be conveyed, silently to tea. His father is coming to town. The son rolls over onto his back and looks up at the clouds that scud by making shapes that a few miles away a small boy recognises as a submarine and a horse.

“Oh good. Oh, perfect. Daddy, oh great”, screams John McDonald-Sayer. No sarcasm here, he means it. He has a scintillating relationship with his Pa. The grand old man of hippiedom who has appeared in the front covers of Time, News Week, Gandalf’s Garden, Oz, and any other publications he’d held a stake in. His quest for enlightenment is as legendary as his fantastic fortune. Whenever he found himself at home with his son, he would play with the boy for hours on end; teaching through play. Endlessly heaping attention, gifts and true love on the lad until the time came to catch the next wave by which he meant, “flight”, by which he meant, “flight on my own plane in my own airline”.

“Stay true to yourself at all times, son”, McDonald-Sayer senior would say. “Find your inner strength peace and power, find your oneness. Watch yourself for the rest of today, or tomorrow. Notice your instincts. Surrender to the now and realise that we are all one. We are all God and not-God, we are all each other”. His Pa had explained this to him, on a hill overlooking vineyards – their vineyards – in the Hunter Valley on a warm October evening on John’s fourteenth birthday, shortly after he’d been expelled from Eton for bullying. “Do not seek to change or understand others. Seek only the truth of yourself.”

“Yes, father. I understand”, they were both very high indeed on his elder’s home grown grass so it did all make sense to him. For too long, he felt as he chewed through the final morsels of a fascinating chocolate bar, for too long he’d tried to be what he wasn’t. He’d tried to fit in with the morons. He had put way too much effort into “altering the perceptions of self rather than the self’s perceptions”.

“Son,” his father took the spliff and realigned his kaftan in movement that simultaneously realigned his chakras, “we need to find the courage to say, ‘No’ to the things that are not serving us if we want to rediscover ourselves and live our lives with authenticity”.

“Yes“, said John, “Whoa.. yes. Not serving us. Thanks Pa.” He took the drugs with a physical effort that lead to a pleasing realisation of this own body was also that of his father.

As the sun set that evening, the father mediated with the Diamond Sutra: he would allow the true sense of self that would elude his son all his waking life to enveloped him. John laid back on the grass, inhaled deeply, closed his eyes and recalled what his Pa had told him a year previously when he had talked of how seeing New York homeless had confused and disgusted him.

“Krishnamurti once said: ‘Let us put aside the whole thought of reform, let us wipe it out of our blood. Let us completely forget this idea of wanting to reform the world.’ It was true, of course it was true”, his Pa had said, looking for his passport.

With deft rhythm , the older man took back the spliff and began inhaling on the in-breaths of a Sutra taught only to the wisest of men in the most secluded of temples.

“The world can look after itself can’t it Pa?”, John took the joint from his father’s hand and drew in its earthiness.

“That’s right son,” his father, who with the rapid, single movement he’d learnt in Tibet, took the joint back, “the world is you, you are the world, removing the conflicts in yourself with remove them from the world.”

Snatching the doobie back in a move he’d learnt at Eton, John revelled in the kind of truths that only a father and son could share, “Skin up, dad”, he breathed.

“Certainly son, certainly.”

Now, ten years had passed and his father is returning from the country. Returning despite the light pollution, “electric germs” and “human stress encampments” that usually keep him away from home. He is coming back to see his beloved boy. John McDonald-Sayer stands up, and waits for Cadrew to come and pick him up. The retainer returns and de-gravels his silent master. They enter the family home.

The house had been moved, brick-by-brick from Somerset in England in 1951. The McDonald-Sayer family had traced a family tree back to 1066 (or at least circa 1066) and the De Kinsey family, and had attached themselves to it. The De Kinseys had, through subterfuge, political wrangling, violence, sycophancy and outright brigandage managed to hold on to the sprawling manse since they’d built it in 1072. For centuries the family had prospered using all the tools at their disposal. But history moved faster than they did.

With Queen Victoria, and the move to manufacturing, came a change in fortunes and standing. This included an Earldom: the First Earl of Cheddar grunted proudly on meeting the Queen Empress, who shuddered and moved on. The farm labourers moved to the cities. The villages that provided respect and hard cash to the family, were denuded of youth, and filled instead with bitter, cider-soaked geriatrics. Of course the family had contacts in Manchester and London, so a move to trade as well as industry was inevitable, as was occasionally failing to dress for dinner.

Chapter 2

Following a disgustingly publicised dalliance with a young fellow in Antibes, the Earl relocated to The Demons Club

With the end of empire and the start of the War to end all Wars, the McDonald-Sayer boys as they now appeared, grew tired of receiving white feathers in the post, and threats of prison sentences. Conscientious objection was often mistaken for outright cowardice in this new world, and no amount of money could shift that so it appeared. Forced into a decision between being maimed in a local gaol or maimed in foreign field, they opted to go to war in the hope that they could manoeuvre their way to the back and some quiet.

All three returned: one, a burbling, shell-shocked innocent incapable of any active function went straight into poetry, dismally and then opened an Art Gallery off the King’s Road in London before taking up the reigns of head of the family on the death of his father by whisky. The second son, syphilitic, blind in one eye, addicted to young boys, had entered the church. The third, and youngest, returned replete with money from deals in Belgium, France and Prussia – family now owned several chemical factories – had relocated North to invest in more factories still. He prospered, greatly, while all around him foundered mysteriously.

With the Second World War came an unfortunately mistimed dalliance with fascism, but so did most of the English upper aristocracy and commercial upper class, and so it was mostly forgotten. The 2nd Earl spent most of his time in London and the Cote D’azure exploring systems at the gambling tables or practising Magick in the hopes of yet more power.

However, following a disgustingly publicised dalliance with a young fellow in Antibes, the Earl relocated to The Demons Club in St James where he proceeded to be shot dead in 1956 by his last remaining son – the impatiently titular 3rd Earl. The 17th Earl had escaped becoming the last aristocrat hanged in England.

There had been rumours at the time that due to a congenital weakeness of the hands, the younger aristocrat would not actually have been able to pull the trigger of the Thompson submachine gun that had splattered his father’s parietal and occipital lobes across the walls of the The Demons Escoffier-designed kitchen. It was also unlikely that he would have been able to simultaneously shoot the old man in the chest with a Luger pistol.

Tragically, all the legal advice provided free of charge by the Yorkshire branch of the family, could not save him from the tender mercies of the Wormwood Scrubs nooseman. The Yorkshire branch had sprung from the loins of youngest of the sons to return from the War to end all Wars. The title of Earl, the house and everything else that went with it passed to him because the Bishop was unable to leave Rome, where he’d fled to a few years earlier.

So, the house speaks of historical precedents, of grandeurs earned over centuries, of honours bestowed and of achievements yet to come. It is called ‘The Glancings’, no one knows why. Its central courtyard, protected on all sides by high walls each cornered by tall, elegant towers, is home to a Go-Kart track, a permanent marquee and several angry peacocks.

Those trinkets are nothing, however, when you experience the 15-metre high statue of the Buddha bedecked each day by new petals and neatly polished swastika; you won’t experience it because you will never be allowed near it. It was not the swastika at the 45-degree angle mind you, but the good one, the nice one, the family having divested itself of its Nazi connections on the advice of their spin doctor.

Mrs McDonald-Sayer spends an hour a day cleaning the Buddha with chamois cloths and warm, soapy water. She whispers even warmer, even soapier entreaties to it, often collapsing onto its lap in fits of desire and giggles. She knows that although the Campbell-Stuarts are a lean stringy clan for the most part, so this statue is as dear to her as the man she truly loved. She calls as “Darling David, dearest Hurst” and loves it as such. He was a boy who she knew when she was a girl. He had disappeared when she went to school in Switzerland. He was somewhere in the world, she prayed.

John heads to his rooms, red-faced, with puffy eyes and a firm requirement to shoot something soft and alive with a handgun. Cadrew follows.

“Why the fuck would someone take the piss out of me like this, Cadrew? My mind is as open as my heart to the truth of the now and the holy me inside. I can perceive and experience Real Moments. I relay the life force. What the fuck is going on that these people should do this?” He slams his foot into one of the cushioned pillars provided for that purpose – outwardly expressing his anger rather than repressing it so that it would grow and infect the authenticity of his life experience – as the sign attached the pillar advises him.

“Maybe sir should call a meeting with the relevant parties in order to ascertain the circumstances under which this, if I may say so, such an outrageous tragedy occurred?” Cadrew speaks slowly as he selects some suitable shootingwear from the sporting wardrobe.

“I don’t want to experience those kind of anti-authentic vibes for fuck’s sake. All that negative energy in one room! Having to deal with small souls would obviously feedback in a severely unwhole way. I’m over it. Let the fucking building take care of itself.”

“Then,” Cadrew lays layer after layer of tweed, and a snakeskin holster across the bed, “maybe a cool way to inject some realism to these people would be to send our person at Hardy, Crum and De Angelis to see them right, if you get my meaning, sir?”

John welcomes a smile into his physical world and casts a nod to his servant.

”Our lady, Cadrew, our woman, our goddess, our Kali. What a bloody marvellous idea, yes invite Ms Belinda Dylan to a meeting with me tomorrow morning at 11:30am.”

Chapter 3

“History? fuck it.”

Left to its own devices, Barleycorn Building slowly fills with the homeless. By the hour it becomes engorged with the wanted, the unwanted, the witless, the weary and the wary. Music thumps from the 21st floor. The walls of the 18th floor are transformed by spray cans, the roof pool fills with the scum of months.

The security guards watch the TV, read true crime and graphic novels; nod occasionally as the stream of new residents is complimented by one more character. They call the occasional internal number to ask that the fighting should not include the ejection of items from the street-side windows; and they direct the pizza delivery relay crews to the correct locations.

The edifice warms, and in its nooks and crannies things are hidden. It echo with stories of both the hard and no luck varieties. Dreams fill its cavities matching themselves to long, secured, comfort-blessed snores and sleep speech.

Anthony John Woods (A.K.A Pokie) sits cross-legged on the 15th floor boardroom table drinking schnapps from the drinks cabinet and throwing spitballs at the postmodernism on the walls. His hood is down, his sunglasses are off, he smells horrific even to himself.

He’d been sexually abused since aged 11, drunk since 12, on the street since 13. He is now 17. He is 17 today. It is 11:30am and he is partying, full of breakfast for the first time in six months. He flicks at the remote control and called up another music channel.

“History? fuck it.” Flick.

“Sport, fuck it.” Flick, swig, smoke.

“A total eclipse of the heart” – What? Flick, swig, smoke.

“Terror alert medium. Campaign continues in the West. Next I speak to Francine Jordan about why banning the writings of Kahlil Gibran in our schools is freedom of speech.” Flick, swig, inhale.

“Anthony, stop changing the channels, man, there is nothing to watch, just bang some tunas on the box. Play tunas for your birthday, Tony, play up, man.”

Under the table, on his back lays Neil Hendle, AKA“All-in-One-Boy” or “Fireman” compressed into a singlet and camo jeans stolen from somewhere. He’s smoking a spliff and trying to read a book on Japanese management theory that he’d discovered the previous night.

“It is my birthday, All-in-One-Boy, my happy to be older day! Pressies and games, bro’.”

“Yes, I know, man, I am totally and completely upon that. It is all good. But how is a man supposed to consolidate his mind on a subject when box is blasting randomness galore into the air? Happy total birthday to you and all that, but that’s no excuse for pollution of the aural ocean is it?”

“Go on then, you choose. I can’t be bothered.” Standing quickly, elegantly from the cross-leg, Anthony John Woods, AKA Pokie, jumps from the table and takes a seat on the floor next to the smaller boy. Handing over the remote he blows a kiss and closes his eyes, “you choose for me. It’s my birthday.”

“You really do stink. There’s a shower behind the mirror over there. All god cons, seriously, I was in there last night for an hour or more, very nice it was with lots with the hot and the cold and body wash stuff. Why not treat your birthday suit to clarification, Pokie mate? At least for my sake because I have to live with you are not easy to love, love, not right now.” Rolling away from the source of the stench, with remote in hand, All-in-One-Boy lays in hope.

“There’s a shower behind the mirror? That’s unusual. How did you find that one out then?” Pokie looks nervously at the enormous wall mirror and then back, slightly less nervously, to his friend.

“I went lurking. Last night, while you were asleep and screeching about rape as usual, I went on a bit of a search and destroy mission. And you should know that when there are mirrors, there is in-aviary something behind them – like magic times.” All-in-One-Boy hopes hard about the shower, his hope is that later on when things got naked and close, he won’t have to hold his nose as well as his dick.

“Walls, man. You tend to find walls behind mirrors. My foster parents didn’t raise an idiot.” Pokie walks over to the mirror, thinks about smashing it with his already scarred fist, looks back at All-in-One-Boy who shakes his head, and so he presses his nose against the glass until the stink of his breath forces him backwards.

“Go and have a shower, man, because sometimes I’d like not to notice that you’d come in. You know I love you, Pokes. But, despite what the world wants us to believe, some things can go too far even for love and, frankly, you have done. Now fuck off and stop analysing what’s behind the mirror, it’s a shower, go into it.”

All-in-One-Boy met Pokie six months previously, so their love was still marching ahead. They had looked at each other and their loneliness had subsided to form a warm, safe place to live just big enough for their cynicism and defences disappear long enough for them to share food. They’d fucked the first night, how ashamed they didn’t feel, how warm and satisfied they did. Then they kept walking together, swapping stories and holding hands, taking what they could from each other, and giving back. They were in love, so the stealing of bags, and the rolling of drunks, the begging and slipping into each others arms in the same Salvation Army bunkbed flew by with the accompaniment of birds and rain.

“It’s my bunk, you fack!”

“I know, isn’t it great?”

“Yes, hold my head. My head hurts and acts up.”

“Why do you fuck around with your words? With the sounds? I always understand what you say, but I don’t get it.”

“I don’t think I do do, Dodo.”

“OK.”

Pokie looks around the place to soak it all up and remember it for when it all goes away on him. This is what he sees:

It is a big, glass room, carpeted and balmy in its never-think-about-it warmth. Red, Japanese-patterned carpet. Injected warmth from the air, when the climate was acceptable, from the mechanics when it wasn’t. It was brilliantly put together, working well, as perfectly as any design could.

(Once every 23 minutes and nine seconds, everything slows down, starts clanking here and there, gurgles and bubbles and generally creates a feeling of irritation. At least it would be a feeling of irritation if you were the kind of person who expected superb pieces of design to work superbly every time, all the time.)

At 11:26am the same day a Jaguar pulls up outside The Glancings. Not one of those flash Jags, spoiler-ladened, bright yellow, modernised and wailing of its owner’s wealth. This was your classic Jaguar. Silver, E-Type. Yelling its owner’s wealth all the same but also taste, great taste, the best taste. Its owner is the company of Hardy, Crum and De Angelis; avenging angels, cleaners, lawyers.

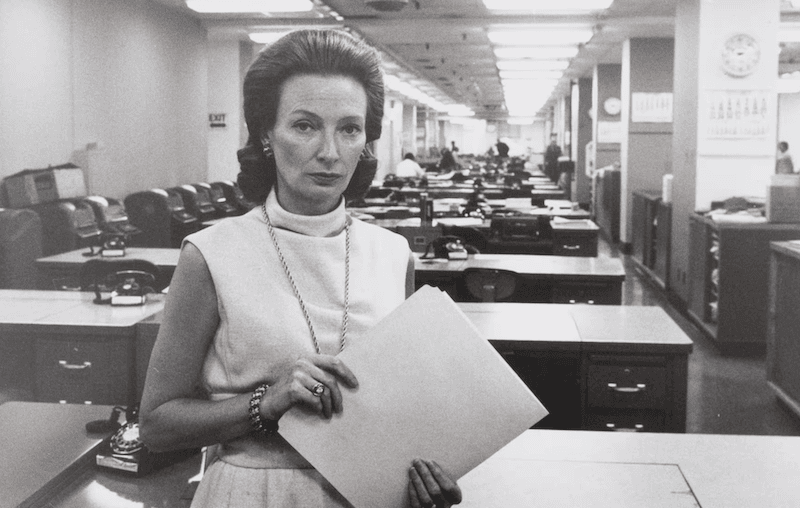

They also own the soul, or near as makes no difference, of beautiful, sharp faced and even sharper brained Belinda Dylan (28) who steps out of the car, immaculate both. A wonderful spinster in the new-fashioned sense of the word. Wise beyond her years in all matters pertaining to living a life to the most exacting standards of look-after-yourselfishness. She is good to her mother and father – still living, on a farm, somewhere deep in Derbyshire. She Skypes them on a weekly basis, confirming her still childless state with a smile in her voice. She sends birthday cards and anniversary gifts, she even goes home for Christmas Day, but is always back in her city central apartments by Boxing Day.

There is nothing cheap or tacky about this woman, from her abstractly perfect diction down to her elegantly cropped pubis. She walks in splendour, everything matching save for one, usually small detail, a broach, a belt buckle, a t-shirt, that she uses like beauty spot. Today her shoe buckles are ever so slightly the wrong shade of grey that they set everything else off perfectly.

Belinda has been the preferred legal aid to John McDonald-Sayer since they met during his very brief attempt to study economics at one of the major Oxford colleges. She was the one who following a particularly heroic sex binge had enquired why somebody who never needed to worry about money should need to study economics. He left the next day, with her card.

Chapter 4

You haven’t neutered him, yet darling, he is still awfully attractive. I love the way he stands there imaging me naked and feeling guilty about it

Emerging from the company car, Belinda straightens her skirt, collects her laptop and mounts the first step at exactly 11:29. Cadrew opens the doors, she plants a warm and deliberately embarrassing smoocher on his cheek, whispers, “What-ho Cadrew, how’s it hanging baby man?” and proceeds up the stairs to her meeting.

“Come in, come in Belinda, sit down. Father is here, he’s doing his meds (by which he meant ‘meditations’) in the east gardens, he will be with us in twenty minutes. Would you like coffee?” John is clad in a very Cary Grant black worsted suit, open necked shirt and sandals. He is sitting in a desk that once belonged to the Dali Lama, his hair is superbly scruffy (to a tee, to a tee) and his skin glows with a ‘just swam 15 laps’ patina fresh from the bottle.

He adores Belinda. Belinda adores John. There is sex tension between them. Their eyes meet like old friends in a Balinese hotel room following an engaging lunch. Their rhythms synchronise as Belinda nods and sits herself down on a chair that once belonged to nobody because it was custom made from Tasmanian old growth forest for her at the behest of John.

“Did you kiss Cadrew again when you came in? You know he hates it.” He slips off the desk and walks across to where she is crossing her legs. He takes her hand and attempts an admonishing expression.

“You haven’t neutered him, yet darling, he is still awfully attractive. I love the way he stands there imaging me naked and feeling guilty about it. I can see the way he tortures himself in his imagination. You know that it’s really abut time that you started him breeding. After all, where is the next generation to come from?” She removes her hand from his and unpacks her computer.

“He’s not getting any younger though. So, we have set in train that he should breed the next Cadrew within the year. We have a fantastic filly picked out for him. One of the Murdoch’s staffers I think. She’s incredibly fit, totally well trained and completely 18. By the time Cadrew is too old for us, we’ll have the new one ready.” He sits on the floor in front of her, lotus-like, looks up and as Cadrew places coffees on the Bauhaus table to his left, McDonald-Sayer begins to relay the necessary details.

“Nice arse,” she comments, meaning it, as Cadrew does his best to exit face on from the room. He blushes and proceeds to the kitchen lavatory.

He flirts more admonition at her, sips coffee and waits for her considered opinion. She looks at the laptop, says a few words to it, nods and then grimaces theatrically at him.

“Oh my dear McDonald-Sayer,” her grimace morphs from the dramatic to the operating theatre, “Oh you have been a silly idiot haven’t you?”

“S’pose so”, he has no idea what she’s talking about, but that’s why he employs her.

“Apparently you decided that you could write your own contracts for this,” she pauses and searches for the correct word, “debacle of a building. Were you sulking with me?”

“S’pose I was.” He often did. He had asked her to sue the family of farmers who occupied a tiny piece of land within the McDonald-Sayer glebe. She had refused. She explained that simply because they kept pigs was not grounds to sue them. He had sworn at her, threatened to get her dismissed, begged her, implored her, swore some more and then sulked all the way to Bali. He refused to talk to her but Skyped her to berate her on this subject, every day for eight months. They only resumed civilised communication after the farmer accidentally fell backwards into his own Massey Ferguson’s reaping blades or something like that during a party.

(The party had been thrown for him by a major super market chain – its legal representatives to be quite exact – to celebrate a pork distribution deal. According to the farmer’s wife at the coroner’s enquiry, he had never touched LSD in any quantity let alone the 780mg that had been discovered inside him post mortem. It appeared to be suspended in a litre of old school absinthe, the wormwood variety that wiped out what the French intelligentsia in the 18th century. The farmer’s family moved from the land following a hate campaign – “Acid Farmer’s Froggie Booze Binge Puts Pox on OUR Porkers!!!” in a national newspaper.

Chapter 5

“Bastards.” She breathes, clenches her fists and biting her bottom lip, “Mendacious, unethical, turdish bastards…

During his Bali dummy-spit, McDonald-Sayer had conceived not only two children but also the grand plan for the Barleycorn Bliding that was to dominate the central business district. He’d decided that, in his own words, he “…didn’t need any help from any long-legged, sweet-smelling, over-qualified bint with an major customer relations problem” and had drafted the contracts.

“Silly man”, Belinda called up the contract from the top secret cloud folder where McDonald-Sayer had stored it secretly.

“Mad man. Look at this. It’s got more loopholes in it than a the walls of a very large medieval castle.”

“Eh?”

She kicks off her shoes and folds her legs beneath her, rests the laptop next to the coffee tray and begins to read:

The party of the first part (she sighs, gently but hurtfully in the mode of an office IT person watching a clerk trying to get his printer to print using slightly dated drivers) being John Marshall Garcia Lennon Donavan Maharashtra Che Kennedy McDonald-Sayer asserts the…

“I have to stop it here. This is disgraceful. I mean, how did you get this passed the other side’s legals?”

He looks down at this sandals and toys with his cup. He looks out of the window and says, slowly and deliberately, “Cleghorn, Barnstable, Groundling and Hayes”.

“Bastards.” She breathes, clenches her fists and biting her bottom lip, “Mendacious, unethical, turdish bastards. You really were having a large sulk with me weren’t you?”

“S’pose so. Soz. Don’t know what came over me. It’s all a bit of a blur. Are you saying that it’s not legal though? That it wouldn’t stand up? Can we get out of it?” He’s up now, on his feet, fighting posture, blood pumping.

She is icy. Still coiled, a drop of blood drips from her lip, settles on her teeth and is washed away by her emerging smile. She is thinking hard. She knows that this many holes can be filled with many dollars. She knows that it will take time. She knows that, aside from yet another tedious case featuring the Murdochs and some question of titles, natives, libels and drudgey drudgey jetting around, she’s not got that much on. She answers, “Yes, baby, yes, I think we can nail these uppity little sods to the wall. We must throw ourselves onto the mercy of the courts. What kind of mental state were you in when you put this bag of nonsense together?”

Chapter 6

In which the police sit back. A party happens and we meet the parent.

The love that bellows its name from the gutters and back alley bars is rough and ready tonight. It’s all the go. It’s up. It’s the love of getting completely fucked up.

“I love this!” yelled Anthony, “I love this booze and shite! I love this music. I love this meat energy!”

The gym of Barleycorn has been turned into a club. Sound systems compete from each end. The basketball hoops contain buckets full of ice. Dayglo paint is everywhere. The old bums are splayed in one corner. The smack addicts are dancing. The speed freaks are dry humping. The acid and E casualties are hugging and screaming and hugging again. The Care in the Communities are experiencing fun. Happy fun.

One sound system is run by an ancient punk whore called Soozie – she’s copping in her head and she’s playing Search And Destroy.

Another other sound system is run by Pokie since its original master – a booze hound called Stuart – fell beneath the working decks. Pokie’s playing We Built This Love on Pledges by the Mighty Solomon Klepto Orchestra.

“This is almost worth it!” yells Pokie.

“Worth what?” All-in-One-Boy, chugs some absinthe he’d discovered in one of the corporate mini bars. He’s gone through every room, gathering up all the booze – and some of the cocaine too – and bringing it down to the gym. You could say that this was his party.

“Worth the police turning up, which they will. Worth a lifetime of degradation and abuse…” he tails of, realises what he’s just said and cues another tune (Tony Touch’s Dimelo Springs Boogie).

“Oh that. Yeah, I suppose it might be.” All-in-One-Boy really isn’t that interested. Introspection, looking backward, analysing shit really isn’t his thing. Right now he’s considering the best way to get the most stuff out of the place before the police do show up and wreck everything. What with the amount of speed he’s taken in the last 48 hours combining with his natural curiosity and greed he has thoroughly scoped the place out. He’s aware that there are some pretty sweet goods to be sold on. He’s also aware that much of it has already made its way out of those imposing front and back doors and is by now being liquidated. This kind of opportunity doesn’t even come once in a lifetime; somehow it has.

“All this chilling and partying is fine and dandy Pokes, but there’s cash to be made here and we’re not making it. Look around you mate, most of these mongrels can’t see what’s in front of their eyes. We’ve got a chance here.”

Pokie doesn’t need to look, he knows that the love of his life is right. He would love to stay here, in this atmosphere, pretending that everybody in the room is partying together and not in their own worlds of schizophrenia, booze, drugs and hopeless numb disengagement. He knows that very soon they will all be back out on the streets, in the Starlight Hotel, due for a fate like Arthur Burrows (burnt to death by four teenagers) or Tim ‘Ziggy’ Jenkins (soda bombed).

All-in-One-Boy’s idea is an obvious one. A good one. Sensible and right. But Pokie wants this idyll to last. He’s not experienced many idylls. Not a single one really. Never.

“Schrödinger’s Cat”, he says.

All-in-One-Boy has heard about that Cat so many times that he really wants to rip its tail off, firework its mouth. As for Schringer or Schroder or whoever the fuck she is, take her outside, douse her in petrol and torch her. As for the uncertainty and the rest of the “sit on your arse and do nothing in case some fragile memory gets hurted”, drown it in a sack.

“Fuck right off, bitch. Fuck you, fuck Schroeder. Fuck the cat. There is stuff here. We can take it. We can make money with it. We can be safe and comfortable.”

“We are safe and comfortable. Right here. We are.”

“We are comfortable, bitch, for now.”

Chapter 7

“I happen to have had a red-hot tip – don’t be so rude – that a rather spectacular coke deal is going to occur very close to the Barleycorn Building…

Now the murk is everywhere and is ready to take everybody unless someone injects an amp or maybe a volt of constancy. Everything in the gym is strangely, Berlin 1920s, disconnected. The scene is a sour one. The space is not creating synergies. Energy is high but negative.

There are two sides to this terrible project though. This deliberately terrible building set in the sea of the centre of the capital city. Clad in cheapness, underpinned by hate.

On one side sit the poor, the dispossessed. Decaying and descendant. Outlines and out of line so we don’t like them and we don’t get them for what they really are. We’ve been with them for a while already, so we’ll leave them. Before we do, you have to know that they do not love each other.

On the other, are the permanently wealthy, always ascendent. What are they up to?

Before we go on though, I have an admission to make to you. I am Pokie’s father by the way. His biological daddy. I am dead, of course – on so many levels. So, most of Pokie’s current situation is my fault. But the honest truth, and I’ve talked to the big boss goomba, the head of the house, the Maker, the People Baker, God, is something about love but mostly, so I’m told, is that I can’t tell you the honest truth. By the way, the police are ready to go. They are just about ready anyway.

Over at The Glancings, John, loves her, Belinda. She loves him. OK, so the dynamic between them is all sheer (as in stocking) transparent (as in the emotions) pretence. Have pity our lord though, what choice do they have? They’ve been targeted since ever they met. Like Pokie loves All-in-On-Boy, John and Belinda do really love each other. That conquers all, right?

“No, Charlie, sweety, hang fire please.” Belinda had been trying to find any mention of security in the drunken contract for the building but she has had no luck. She rushes through pages on the off chance that amidst the paranoid, BBC law court dramatics that masquerades as a contract she can find anything whatsoever, at all, anywhere that would suggest liabilities against the security firm (on a rolling contract), the door or lock or lintel or window manufacturers. She can’t.

So, she’s Zooming with Charles Drake, friend of uncle George, owner of race horses, and also rather conveniently rather high up in the strong arm of the law of the land. If he can’t help, then her next call is to Francis Moore MP, the Home Secretary, and another former lover. She wants to clear the Barleycorn out. Knock it down. Sell the land on for a profit, and forget the whole sorry saga.

“Charlie, aren’t we in a more caring time? We are. We need to build housing for real people. But right now, we can’t winkle out the pestilence in the corrupt high rise we worked so hard on”, she waited, tapping her head as she looked at John who was snorting a line.

She continues, “I happen to have had a red-hot tip – don’t be so rude – that a rather spectacular coke deal is going to occur very close to the Barleycorn Building at circa quarter to eight this evening”, she didn’t. I didn’t matter. She was passing on a tip. He needed arrests.

The more she examines the contract, the more she is reminded that John, bless his silken socks, is a child. One could send him in, head-down, tears bared into a fight and he’d do his best. He might even win. But this time, he didn’t quite get that there was no winning at the outset, it was a legal contract.

She listens to Charlie waffling on about the this and the that and the complexities and the having a drink later in the week when time did not contend and, ceteris paribus, all would go well. She makes familiar sexual noises and reads and reads and reads. He talks and talks. She stops.

“What was that Charlie?”

“It’s this thing you see, Bel, as far as we’re concerned, Barleycorn Building is a perfect right now. It’s attracting all the right sorts, if you get my drift.”

“You mean you’re not going in?” She’s confused, she likes to be confused.

“Well, no. Not right now. Not for at least a month anyway. It’s actually working out quite nicely. I’ve got the Bobbies at the ready but there are”, he pauses, “some issues with pay negotiations you see.”

“Issues? Pay? These are public servants” she is genuinely appalled.

“I know. It’s bloody outrageous. But our lot are a hair’s breadth away from being in the Barelycorn themselves most of them. The bloody whinges of my own mob takes up more time than the actual job. The less I actually make them work, the better at the moment. Tell you what though, I’ll put it about that we are going in? How’s that?”

“Bless you Charlie. Bless your heart. But what do you mean by putting it about?”

“Like you don’t know.” He winks, aural like.

“I’ve already said stop the Benny Hill.”

“Talk to our media chums.”

She hangs up. She makes another call.

“OK” she says.

She hangs up.

It is 4am.

Chapter 8

In which music, art, theft, drugs, life disappear out the back door. I dislike All-in-One Boy. And hope starts to grow in The Barleycorn.

The great, already crumbling building is mooned by the moon. Pokie is asleep. All-in-One-Boy is very much awake and stealing a lamp out of the door to a pile of goodies he’s curating for later selling on Jimmy the Fence in Highgate. He’s piling it on top of the chairs and paintings already there. He wants Pokie awake to nick a van. He can’t drive. He doesn’t want to be burned in a gutter like Burrows. He moves fast, but is slowing visibly.

At The Glancings, Belinda is racking her considerable intellect in order find key elements like cooling off periods, descriptions of works, service level agreements. She had discovered something about payments but despaired that it described how they were all to be made in advance, “because I can afford to, yeah!” as the rubric so inelegantly laid out.

In Belinda’s head is Stoned from Dido’s Life For Rent album.

John is bedded down, the hookah bubbles away by his vast, 1,001 Nights styled bed, the hookah hose rests on his chest. He is snoring on his back, a very regal, very assured, starfish.

In John’s head a usual is, Fix You by Coldplay.

Nothing plays in Pokie’s head. He still stinks to hell or high heaven and he is dreaming about his family. His father died (that’s me) when the boy was 18 and already gone from the family home. Pokie had been fostered at 14. His mother had gone somewhere or other. Dad stayed on at the family home, smoking blow, watching the telly, listening to old Punk Rock albums, betting on the dogs, flogging stuff off and holding onto other stuff for various acquaintances.

Pokie is dreaming that he has to drop by his Mum’s. The house is always immaculate – in reality it was always immaculate before she left and died of a broken heart and knives late one night in a park walking back from her second job.

He sees his father (me!) there, spliff in hand, Don’t Dictate blasting away, vacuuming the hall carpet. He exchanges some US dollars and moves into the kitchen where the old man is bleaching ashtrays, spliff in mouth, whispering, “Which one of you bastards hurt someone near and dear to us. Come up here and we’ll kick the shit out of you, you bastard!”

He buys an eighth of hash with the money changed and slips upstairs to the bathroom to skin up. His father is brushing and Ajaxing the lavatory pan, shouting “You’re in a rut! You’ve to get out of it, out of it, out of it!!”

“Dad, why are you always cleaning up?” he asks dream Me.

Chapter 9

At home in Algiers, the once hesitant architect checks his watch and begins to laugh, and laugh and laugh and laugh until he is sick. Actually sick.

An amateur band starts to practice in a nearby yard. I continue to scrub and shout. Pokie slips out of the dream and rolls over.

All-in-One-Boy, still moving faster than you or I would consider decent at this time of the morning, he is unscrewing art from walls and stacking it in the service elevator. He already has Jimmy the Fence prepared to move the gear. The paintings are amazing, there’s a Jenny Watson, a John Brack; he knows this because every one of the motherfuckers has a little card next to it saying what it is, who its by and what it’s supposed to be about. Albert Namatjiram, Chris Ofili, Caroline Zilinsky, Renoir, Damien Hirst, Chris Pignall. Circles, sheds, dots, more dots, portraits, landscapes, money, money, money.

The heating kicks in at 4:30am as the shuts off with an explosive percussion that wakes many of the gym sleepers briefly. The building’s shutters come down as the security cameras black-dot in sequence. All the tapes are wiped and the fire-safe sprinklers shower the kitchens with detergent. Freezers either ice up or start slowly cooking their contents. The building is eating itself, it hates itself, it was made that way. It had shit parents.

At home in Algiers, the once hesitant architect checks his watch and begins to laugh, and laugh and laugh and laugh until he is sick. Actually sick.

I’ve realised that I’m looking in on all of these people for a reason. Obviously I keep a weather-eye on Anthony because of our relationship. In so doing I can’t really avoid inclusion in some of the life of the little turd, Hendle. I don’t like him at all. There’s something sneaky about him: All-in-One-Boy? What kind of a name is that? A wanker’s name.

The actual fact is that he’s only as waif and stray as he wants to be. Unlike my Anthony who is your actual orphan, that other toerag is living the life predominantly to annoy his parents. That he could leave it at any time, that doesn’t sit well with him or me. The fact that he has no soul is not a good sign either.

That happens, being born soul-free, it’s not a mistake or anything, it’s due to one of two things: either (a) the soul is already as full as it can get with lessons learnt and experiences earned but the owner of the soul hasn’t realised this and still wants to go around again (often this ends in suicides and at an early age – I mean you would wouldn’t you, once it’s become apparent that you’re just treading water, you’d move on; (b) it’s sealed itself up and in so doing it has withered away to nothing.

This often results in suicide as well, but more often than not in massive amounts of excess, of pouting and sulks, of getting your own way for the sake of getting your own way. You’re not able to let anything else in to charge up the old karmic (or whatever you like to call it, the big boss is quite free with terminology so don’t worry about it over much) so it’s all out-out-out. The whole soul thing is, if I’m honest, a bit out my league at the moment. I’m still floating about a lot trying to get a handle on the general after-life concept. It’s not as straightforward as you’d like to think. But that’s my story and you’re not here for that.

As for John and Belinda, I’m damned if I know why I’ve got an oversight on their goings-on. I opted out of the whole, “seeing the future” thing on advice that it would be a bit of a culture shock. Tried it once, and the advice was spot-on, it made me incredibly nauseous, all time mixed together, choices required as to exactly which future I wanted to be able to see. I’m not good with choices.

Now, the curious architect. I can see him right now in an apartment in Algiers reading the paper and drinking a daiquiri, he’s got remorse in his veins and it will not let him go. All the laughter in the world is not going to rid him of his natural good nature. He’s even started sending what he thinks are anonymous cash donations back to his ex-girlfriend bless his little heart. For now, however, he’s avoiding the remorse as it makes its way remorselessly (as it were) to his spirit and hence to his soul. He’s pretending that it’s not remorse at all, its power. He’s got the power now to brighten up or tarnish other people’s lives. His decision all backed-up with the almighty buck.

So, why do I have oversight? My guess is that the law will come into play, probably around that fucking abysmal contract and that Anthony will have to fight the good fight. As I am attached to my boy, it looks as if he’s getting attached to these others. He’s getting quite attached to the place as well. He can see in some of the folks around him that they are too.

Chapter 10

Two bums are having a real go in the kitchen as well, cooking up a storm.

Right now, there are 423 people in the tower. Well, 439.5 if you deal it in the pregnancies, and no I am not going near that one, I’ll leave that to the powers that be. 423 people in less than two days. That’s some serious pulling power this building has. “Indian burial ground?” you think? Take another guess, for a start this is not the United States. “Ley lines?”, possibly, there are so many of the fucking things who can tell? No, I really can’t tell you, just be satisfied that it’s happening, that the people are coming in all of their colours and shades.

I can see them, I move relatively freely within the limits laid down for me and at my request, and I can observe them. But I can’t see into them, not unless they make a connection with the one I should really love.

The artist colony on the 21st floor is really starting to make a go of it – there’s already a performance in planning. OK so a number of them are fellow-travellers, wankers and the usual kinds of wannabes that mistake splashing some gloss around on a wall for communicating a vision. But there are some good sorts up there.

Two bums are having a real go in the kitchen as well, cooking up a storm. They are going to be well pissed off when they go back there later today. But they’re developing a stick-at-it-ness.

There are students in the penthouse, nurses on the fifth floor, asylum seekers in the basement (natch), divorced, middle-aged men in the games rooms on the 17t floor, divorced, middle-aged women all over the ninth, tenth and eleventh floors, and there are ghosts all over the shop – seriously, the newsagent on the mezzanine is overflowing with spirits.

It’s a bit of shame that so many ghettos should happen, but that’s people for you. It’s 5:30am in your earth time (I love saying that) now and the heat (in your earth therms, OK I’ll stop) is pretty unbearable, so people are waking up and wandering around, bumping into each other because it’s dark what with there being no light and all the shutters having been closed. Everything is compressing and over-heating.

Chapter 11

In which we discover choices can create inauthentic moments. And smell can override all other senses.

A month has passed. My Anthony is dead. Still not here though.

The wealthy cowardly architect is on the telephone. He’s been called up by Cleghorn, Barnstable, Groundling and Hayes, solicitors at law to attend the inquest. They are advising him of sticky situations, of possible wrinkles and potential liabilities that could not have been foreseen. The architect is listening, vaguely. His brother, the accountant has already salted away the lottery win and the payments received for Barleycorn.

“We may need you to return within the next month in order to help out in the courts.” Junior lawyer, Sam Wells, makes it all sound so blasé but he’s got his finger inside his collar and is pulling for fresh air, needing it to hit his inflaming razor burn.

“I don’t think that’s going to be possible really. I’m planning to go to Verbier for some skiing prior to Christmas. I’ve really got nothing to say anyway. I’ve given up architecture. I’m writing a novel.” He gazes out of the window at the sky.

Junior Wells wants to say, “Oh go on!” but knows he mustn’t. He’s also concerned that the architect hasn’t asked to speak to someone higher up. Clients always ask to speak to someone higher up. Wells is not comfortable with actually speaking with these people for more than a few seconds. He’s certainly not good at convincing them to do something they patently do not want to do. He consults the script given to him by Mr Groundling.

“Let me assure you, sir, that returning as requested by one of our very senior partners, will certainly be of immense benefit not only to yourself but to the cause of justice. Sir, you will be contributing greatly to the overall wellness of the world in which you are living. Making the sacrifice you are going to make to”, he consults the notes again, “not go to, to miss out on going to skiing, sir…” off he trails, unable to keep it up. He waits.

The architect is aghast. He’s just seen two planes seemingly missing each other by a whisker out of his window. Or he thinks he has, the total and complete lack of stress he feels about everything has been making him hallucinate a little recently so he can’t be sure.

“What was that you said. Something about making the world a better place by going skiing?”

“No, sir. I said that you could make the world a better place by not going skiing. By coming back to contribute to the cause of justice that is. Sir?”

The architect looks down at his espadrilles and thinks for a while. As soon as the sound of Junior Well’s rabid pen tapping stops he knows what decision he has to make.

“OK, I’ll come back.”

“Pardon?” Briefly, Wells waits for the inevitable caveat.

“I’ll come back if you represent me.”

“I don’t think that will eventuate, sir. I think that a client of your import will be handed up, sir.”

“Then I won’t come back.”

“Can I consult for a moment please, sir?”

“No.”

A fix. A right fix. Time to make a decision that could result in either a great deal of responsibility or a great deal of lost revenue. Either way, Wells reckons, it’s going to result in a great deal of unwanted pain. He closes his eyes, tries not to think, tries to let the words comes come from him. This is the kind of chance that comes along once. He’s been told this on numerous occasions by numerous bloody people who won’t let him alone to get on with his reading and his music. He has to let his true self make the call. He breathes out, calmly.

“I’m afraid, sir, that I’m not in a position to make that call. Do you want me to hand you up to a person of more authority?”

The telephone goes dead. The architect sits back and reviews the sky. Not much more has happened. He starts to count his cash-counting pile, this time organising it into notes that are less damaged on a sliding scale beginning with the top, right corner and excluding graffiti has a parameter.

Junior Wells stands up from his desk and walks towards the door marked, “Mr Groundling Sr”. He knocks, enters and observes Mr Groundling removing his earpiece.

Chapter 12

He is smiling displaying wonderful teeth – the kind that should belong to somebody at least fifty years younger than his seventy years (they do).

Groundling is a fat man with an enormous head and fingertips the colour of old scrolls. He is dressed in black with a collarless shirt open at the neck. His suit is the thickness of cartridge paper, it is flecked with white flakes. He sits in a modified and extremely high-backed, Charles Rennie Mackintosh Monk’s chair with no upholstered seat. He is not scowling.

He is smiling displaying wonderful teeth – the kind that should belong to somebody at least fifty years younger than his seventy years (they do). His desk is embedded with three 17-inch plasma screens – big desk. The telephone that feeds the earpiece is hidden. His legs never move. He is entirely stable.

“Other people are laughing at you.” Groundling bends towards the desk, slams both fists down. Leans back and shrieks, “Other people are laughing!”

Wells turns around and leaves the room, leaves the office, leaves the street. He heads towards the the remains of Barleycorn Building. Five minutes into his departure he realises that he’s left his sandwiches in his desk drawer. He turns, returns, enters the offices and experiences the feeling he used to get when he’d pop in on a Saturday to use the computer. It must be the same feeling, he now realises that refugees get when they go home after an absence of 10 years; you know the place, some of it is familiar, but you’d really have to want to be part of it again, because it’s got a life of its own without you, and you’ve had a life external to it. He takes his sandwiches, places his mobile phone on his desk (now only the desk) breaths out and rejoins his previous route.

As he walks he finds that he is terrified and happy. He notices the street signs, the cracks in the pavement; he starts to jump to avoid them, to avoid the devil breaking his mother’s back. He can see The Barleycorn. He is approaching from its south side. He can see some banners but he can’t read them. He can smell coffee and garlic. He looks a pretty girl in the eyes as she approaches to walk by him, she smiles at him confidently and continues. He smiles back. He realises that she’s smiling because he is jumping cracks. He is nineteen years old. He’s actually quite alive and very poor. The coffee and garlic are delicious.

He reaches the place where the the doors of The Barleycorn used to be, the revolving doors that would accelerate and send people spinning into the atrium are no longer there, he steps over the threshold. Despite the residual tropical Singapore-in-summer humid hea, he feels very much at home. He sits on a crate near the shell of the vacant front desk, he leans down and puts his hands on the blackened and cracked marble floor. A hand covers his hands.

He looks up and sees a girl in a tracksuit. She’s asking him for money for a dance group that are going to travel to Australia. He says no for the first time ever. She moves away to two old fellas sitting by the Westside entrance eating a porridge of some kind. He waves at them all and replaces his hands on the marble floor. They begin to play a song on two battered guitars. He has no idea what the song is but he lifts his head up to look at them. The girl is singing now, so slowly that it could be Billy Holiday rendering Strange Fruit to God himself or it could be your ideal mother singing a lament for the death of your ideal self.

People come down the stairs, there are not spinning elevators left, they are silent. The evening comes in as the heating moderates.

“Want some gear bro?” All-in-One-Boy is there. Emaciated, a bit charred but keen as mustard, “Want some gear?” he asks Junior Wells.

“Gear? Drugs? No thanks.” It’s been a day of No for Junior Wells and he’s getting a bit over it by now and he really does not want to start the slow descent into the hell that is drugs.

“Oh, go on” for All-in-One-Boy, “no” is water and he’s one enormous duck’s back, “It’s nice. Don’t believe the hype and all that, the only reason you’re saying no is because you think you should. Why not try to experience something for yourself, eh bro? Or maybe,” he says, moving his feet like a billion-dollar sports star, “you’re not ready for it.”

“No he’s not ready for it.” I say, but he can’t hear me, obviously.

“Do you want to get high?” Hendle asks Wells.

“No. I don’t know.”

“Fuck you, mate. This is fucking business. Fuck off, man.”

“Are you talking to me?”, I ask.

“Yes, of course. Fuck off”, I am stunned.

Now, from where I’m sitting, his has all the makings of a fight. So, I’m going to lean into this little turd and tell him to walk away. The little All-in-One-Boy-turd will be nasty – and not in a good way – out of sheer desire for power. Anthony has been stabbed or burnt or crushed or something.

Chapter 13

Selfish? Me? Of course I bloody well am.

I can’t deal with him face to face, mano-a-mano right now. OK, I’d be able to let him into a whole bunch of perspective about the eternal this and the interacting life forces of that, reincarnation on demand, all that stuff, but he’d ask me some hard questions that I honestly do not have the answers for yet. He’ll ask me why he never had a chance and why I left, why his mother left Sure, I could send him off to a deity or saint who could lay it all out for him, but where would that leave me? Anyway, I’ve not seen him.

Selfish? Me? Of course I bloody well am. So are you. So let’s not fuck around with that particular area of debate shall we? It won’t get either of us anywhere. I want to make my son’s afterlife a happy one. Just not right now. If it isn’t obvious by now that I stuff things up. So, now just give me time. Can you hide in heaven? Yes. Is this heaven? I don’t know, do I.

All-in-One-Boy looks at me, looks back at the marble-clutching junior lawyer, thinks about just how much he misses making love to Pokie and he backs away. He goes to cry. He misses the boy, I’m hiding from. Ironic that.

Chapter 14

In which there is a death in the family.

John McDonald-Sayer is getting out of a Mercedes. He is taking the air. There are olive and orange trees around the front of his father’s house. There are mangroves to the east and west. Each has its own eco-specific system, never the twain shall meet.

His father lives alone save for the all the house staff who he keeps on as long as they meditate with him in the mornings and evenings. He supports them, six of them and their family. He ensures that they are home-schooled, clean, well-fed and above all else, he ensures that they are centred. He never asks them to do anything he hasn’t already done, from chopping wood to making paella. He pays them well and is prepared for them to leave at any time. He is self sufficient in all things.

He is in bed right now. He has had three strokes in two weeks and he wants to stay alive for his child or someone. He talks to another child, one he killed. It is a private conversation that he is taping on his Chilton 100s reel-to-reel tape machine for later inclusion in the “Archive of Authentic Time”.

It is a private conversation.

John marches into the house and sits on one of the beanbags that is close to a landline telephone. He’s come to ask his dad for some advice. John’s used to waiting for his old man to appear. He’s had occasion to wait for a week before, but this man is the only man he is prepared to wait for. Anyway, Belinda is due to arrive in seven minutes and she is always on time so John won’t have to be alone for very much longer.

He needs to know whether to bother with the Byzantine complications that Belinda has presented him with or just to own up, blame the architect and push through. On the one hand, John, he’s got enough everything not to have to bother with anything. On the other, he is angry, someone has taken the piss. Someone has interfered with his balance and that could mean that he has a chink in his armour that could somehow impede his progress. No matter how much stuff he’s got going on: spiritual, temporal and material, he seriously doesn’t want to repeat himself in this life or in any other.

Having reviewed his life constantly in trips, hypnotisms, hash acid meditations, sensory deprivations, sensory overloads, fasting, Blakeian excesses, trances, transcendentals, Endentals, cold, heat, sadism, masochism, primal therapy, and driving fast with chicks on his dick, he is aware that repetition without the correct underlying vibe is the deadend of universal truth. His dad has told him so too.

He meditates until Belinda arrives, which she does in seven minutes later.

She has been working hard, taking the dog – Carol, after Carol King – out for walks since 6:30am. She got in her car at 8:30. It’s Saturday and she’s arrived at 2:30pm. She is in a foul mood, having had once again to review notes on land leases provided to her by a senior – wrong, again.

She wants a drink, a movie, a swim and not much else until at least this evening. She knows, however, that she has to draft a last will and testament, and that is always wearing for everyone concerned. She also knows that Barleycorn Building is going to cost a great deal of compensation money even though the dead and injured were all homeless, mad or both, and consequently of no real value as even they would admit.

She enters the house, kisses John on the head, “He’s asked me to go straight up, read this and remember as much of it as you can”, she says as she heads upstairs.

“Eh? I didn’t even know he was here yet?” He drops the thing she’s given him to read.

“Did you bother to go and see,” she asks from the top of the stairs. “He’s not well. He’s dying.” She goes into the bedroom.

John is wondering whether or not his father dying is a good or bad thing. After all, the old man has been banging on about moving on to the next stage for as long as John can remember.

It’s going to mean quite a large gap in his life. Probably going to be bigger than when nanny passed or when the grandparents ploughed into the mountainside on the way to the Buddy Holly convention. You’d have to assume so. John isn’t entirely certain. I’m sure. It will and he will make the most of it until the day he too dies, and that’s not telling the future, it’s common sense.

On the one hand, no more Pa to talk to.

On the other, there are the additional funds to consider, unless Pa’s gone and made one of those “give it all to good causes”, which is unlikely. The will! Belinda’s got to be here to sort out the will. John moves rapidly to the kitchen where gets a servant to sets out ginseng tea things and arrowroot biscuits as the kettle boils.

He selects a suitable face from the armoury, not too sad (he might not be supposed to know) but not too much levity either (he might have been supposed to know). He gets the servant, Ming-Ming or Pan-Pan or some other panda bear like name, and makes his way sadly but not too sadly, to his father’s futon which is placed out on the wide, wooden, west-facing balcony.

Chapter 15

Belinda at the foot of the futon can’t help herself and makes a derisory eyebrow raise.

Pandit Vasant Rao Kadnekar is vocalising on some old vinyl in the background as the Jasmine and Jacaranda blur the air. The old man is sitting up on a pile of comfortable cushions on his futon. His eyes are closed and he looks very old. He has been tearing the hair from his beard and head because he can no longer speak and this is frustrating him. He is tapping out messages on a Stephen Hawking voice machine.

“Mumma must be looked after at all costs. She can’t look after herself. We must make sure that Cadrew and offspring Cadrews are supplied with everything they needs to maintain the house and her.” It sounds like an adding machine making sure that compensation payments are ordered for its family of calculators.

John stands in the doorway. He is shaking. His father’s calming voice gone, which sort of answers his earlier conundrum.

“Look after the animals. Make payments to petting zoos as mentioned in earlier correspondence. Make provision for house staff. Make provision for schools in Calcutta, Dhaka, Darwin, Birmingham and somewhere in Vanuatu. Maximum class size is 20 pupils. Curriculum as previously outlined. Only the poorest need apply.

Make provision for LSD research. Make provision for cannabis and hemp lobbying. Increase security in Tasmania. Increase security in Arkansas. Submit all rock, Beat and trek memorabilia to Powerhouse Museum, Sydney. Submit all the Burroughs crap to British Library (that should annoy them).” He tries to laugh but the stroke has paralysed his left side so all that happens is a lop-sided leer.

John moves forward rapidly and, placing the tray on the low side-table designed by George Nakashima for Pa McDonald-Sayer personally, he sits at his father’s right hand side.

“What about the me, Pa? I have a court case to fight”, he pauses and looks to Belinda for advice, she frowns, he understands. He continues, “Don’t die, dad.” He says. This is the moment of truth. Ask the question.

“Don’t be concerned about the material things, John”, rasps his father’s voice-box.

Belinda at the foot of the futon can’t help herself and makes a derisory eyebrow raise.

“I won’t Pa. I’ll be fine, really. I’ll look after mumma.” John’s in tears. Real, whole tears are coming from him and he has no control over them. He’s noticed the scars on his dad’s head and face. The man has shrunk and now appears to be the short man he actually is. He’s wearing an extra large t-shirt with a mandala printed white on a dark green background and the neck ring is somewhere near his nipples. His neck itself is all vein and sinew connecting with his shoulders like the root system of an ancient tree connects to the ground.

John honestly can’t stop himself from sobbing. He’s trying to catch his breath and at the same time he’s realised that he’s cradling his father’s head in his arms and stroking the old man’s hair. Pa’s breath stinks to high heaven. It reeks of garlic, coriander and rot. Sliced up, harsh groans come from inside his mouth and John thinks that he hears words that he can’t translate but can understand. Long sentences packed tight.

“Of the peace of the peace of the peace of the peace…” he thinks he hears. But he doesn’t, I’m telling you.

Belinda walks to the edge of the balcony, looks into the trees, the canopy constructed for the birds and monkeys. She’s never liked the old man; too full of shit. All this maudlin crap is wearing her down. No more than a sentimental attempt to draw some particular closure to a life that has basically been thrown away on a search for life. She’s seen the books, and the old man has contributed nothing to the family capital that already existed. OK, most of the time he’s lived on the interest, give him that, but as for providing more value, it’s not been that sort of a quest. She doesn’t trust quests. They tend to be open ended and more about the journey than the goal. Goals are what make the world turn. Journeys are time wasted on views of passing things.

All she can hear is crying and gurgling. Whoever said it was right, we do go out the way we came in. Babies in and babies out. She also wishes that the annoying, whining, music would stop. She breathes gently and snatches a look at messages that have appeared in her silenced phone. She texts back responses to dry cleaners, the garage, her new literary agent and the caterer. The sounds from behind her have quietened. She turns around and sees John, foetal – as is his wont – with his father’s right hand on his son’s ankle. The left hand is slate. His face is flat and grey. His eyes are milky. He moans.

She returns to her position at the foot of the bed, opens the laptop once again, and he continues to relate his last will and testament. The sun is setting as a fight, a monkey fight, breaks out in the trees. They are fighting over food or sex or territory or something that can’t fight back.

The music stops.

She looks through the record collection wishing that someone had ripped the lot to a decent format instead of this aged nonsense and finds an LP at random. She puts the stylus on down and as the noise begins she enters her own escapist state.

She don’t like the music, she doesn’t like the words, she doesn’t like the sentiments,

Well, money certainly can buy you love, she thinks.

The old man has sat bolt upright and is typing, “Ha ha ha ha ha ha COME HERE hah hah haha” incessantly on this keyboard. Belinda stays exactly where she is. Deathbed scene or no, she has no inclination to find out what’s he’s on about outside of the business at hand. For all she knows another tiny but massive explosion has occurred inside his brain and he’s turned into some spastic sex attacker. Or maybe he wants to impart yet another truism.

John is silent, foetal. She looks the old man in the working eye and spits at him, full in the face. He can’t move to wipe it away.

“You never really did anything much did you, Stephen? You just soft-cocked your way around the world visiting all the places that you figured were The Places. You’re a spiritual tourist aren’t you? A godless dilettante. As for your family! Your wife fucks a monumental Buddha in your own front yard and your son, well, he’s the spitting image of you.”

He waggles a finger and begins to type once again. “Please turn the music off.”

She doesn’t.

He continues, “You’re one hundred percent correct and at the same time wrong. Stop raising your eyebrows like that. I didn’t…”

“Want to be born into wealth and privilege.” I’ve heard that one. You said that one in Montreal, in your house in Montreal, or was it Mont Blanc or Monte Casino, I forget, there are so many of them, one of the ones you fucked me in.

“No, not that, you stupid girl. I didn’t have to worry, so I didn’t worry”, he machines at her.

She frowns.

He backspaces over what he was going to type next. It’s dark outside now. The automatic lighting has come on, all very sombre and slightly golden. Jani, one of the housemaids puts her head into the room and decides that it’s not her place to interrupt such an obviously holy moment. She backs out and goes back to the kitchen to continue watching Punked while reading a gossip magazine. She’s laughing at the pictures of the fat women gone thin, and gasping at the dashing men gone bad, and generally having a lovely time with her sisters.

The old man types and his mechanics speak, “As for the family money, well, when it comes down to it there is only so much you can do about it.”

She frowns again.

She’s enjoying this. He’s about the die and she’s here to see it.

Chapter 16

She finishes a second vodka and pours a third. She puts on another record.

Belinda gets herself a drink. A vodka. Ice. She looks through the record collection, her back to the old man. She knows that there must be some cocaine in the house somewhere. It’s a comfort to her to know that she hasn’t gone looking for it.

Her plan is to abstain for a while. See if the brain still functions at a higher level that way. She sips and recalls that the old man had suggested that idea to her. She’d expected him to be a stoner, but he’d quit the lot in 1974: booze, drugs, fags. He kept booze and drugs in the house to challenge himself and, in my opinion, to watch other people do them.

I’ve seen him, alone, spending long evenings skinning up endless spliffs and placing them around the house, then counting them again the next day, the next week, the next year. Chopping out lines and putting them in custom-made glass tubes. I’ve watched him soaking incredibly beautiful pieces of paper in Owsley’s acid. I’ve seen him decanting bottle after bottle of wine and spirits. He cries his eyes out when he does this. He won’t be doing it again.

Over the years she’s had a few conversations with him, usually when John wasn’t there, that lowered her guard to critical levels. He could act the role of really lovely man. She takes a sip. She remembers talking to him about abortion and love. Those two separate conversations got to her in tears and decisions.

She finishes a second vodka and pours a third. She puts on another record. Back to the old man. Her back to the old man.

“Why are you doing this to me?” The lack of an inflection in the voice makes it easier for her to interject her own feelings into the query. She doesn’t answer, there is no possible point to an answer. She hasn’t thought one through. She really does want some coke though. Short burst energy with dangerous history. It would take her mind off the matters in hand as she considers:

Will it be it any good?

Will the rush be depressing?

What will this rush be like?

Aren’t all rushes the same?

How beautiful am I?

Do I need this cigarette?

Could I handle crack?

Do I need to fuck John one last time before I get married?

Did all those people really die in the building?

Am I a good person?

Didn’t Freud recommend coke for therapy?

Do I look OK?

Does that matter?

Do I look good?

Do I look great?

What is he saying…

Introversion at warp speed. She’s trained herself to do that. She doesn’t take any because she asked enough times to know the answers. She’s made a decision to keep at arm’s length those things that limit her. I don’t blame her. I’ve gone back over her catalogue. Believe me she’s got no reason for comfort in a deathbed scene, which between you and me is where she is.

Chapter 17

These people are not to be trusted ever. The only ones worse are the middle classes because they are so incredibly dull. Watch the toffs, Belly-girl, watch them close.

Family members died on her like a pigeons fed poison bread by crows. Dropped at her feet one of them, an uncle, did. Cracked his head on the fridge as he fell with the aneurysm bursting. She was or is twelve. Pardon my inability to deal with tenses – death does that.

The family deaths come as one six-month event when she’s twelve: Grandma Burton, Granddad Burton, Uncle Charlie, Uncle Phil, Aunty Sharon, Uncle Bill, dad, Uncle Bill, David, Grandma Dylan. At Grandma Burton’s lying-in, she curses God, challenged him to a fight she knew she couldn’t win, cries and swears in the church (all in her head).

At Uncle Bill II’s funeral a reaction was born in her that getting too close to these people would lead to more tears and hurt. She decides to better herself as an act of defiance against the Santa-faced big boy in heaven.

I’ve seen a conversation between her and the old man in which she related this story and he’d intersected a question about her distinction between “a reaction being born in her” and her “making a decision”. She got stoned. I would have as well. Way too nit-picky for me.

Belinda emerges from her reverie. She finds that she’s scared.

There is this bloody figure – a man who has featured as prominently in her life as her own father dying in front of her, and then what?

She shakes herself down. A water. Cold. Swift. Back to the old man. Her back the old man. Here’s the situation in her mind: the immobile, foetal son whimpering slightly and then silent. The fighting monkeys screaming at each other as they tear something apart. The sickly yellow ambient light that doesn’t light the room. The inane laughter, or the laughter at the inane, from the depths of the house.

She drinks her vodka and pours another. She keeps her back to the old man. No matter what he’s got in mind, she can take him. If he’s genuinely ill and has come up with this, admittedly out of character, arrangement it’ll be even easier to take him down. She works out and has decades on him. He’s weak, always has been.

She can take John as well. No problem there. She could probably take him with one sharp word to the brain. He has to be ill though. No one would deliberately get themselves into the state he’s in for a gag. That makes things more complicated. That adds levels of unpredictability above those usually exhibited by the spoilt brat brigades. These same brats are deeply unpredictable – after all, they set the standards for behaviour and to be able to set one standard is to be able to dismiss another. Belinda knows not to take anything at face value.

“These people are not to be trusted ever. The only ones worse are the middle classes because they are so incredibly dull. Watch the toffs, Belly-girl, watch them close. They can go years and years without showing their colours, but one day ‘Pow!’ and you’re forgotten. They’ll break your fucking heart and then ask why you’re not laughing along with them about it.”