The works of sin – failed projects

One of my sins is one of overwriting. Over-plotting. Adding things rather than elegantly reworking the writing in the edit. Enough theory. Here are the bits and pieces of novels, short stories, and poems that never quite achieved the required clarity.

Barleycorn Buildings

The first few chapters of a novel that ever had the chance to end about family, ego, homelessness and hubris.

The Assumption

A novel that never quite made it. It was about love, hope, self-image and memory’s false constructions.

The Little Man

Nobody he knew would have dared to steal Keith Kinsey’s car. Like his house, his holiday villa on the south coast, his children, his wife, his space at the greyhound track, even his seat at West Ham, that car as sacrosanct. Do not touch. On pain of death, or at least torture. Kinsey stood and

Writing, fiction, novels, short stories and poetry that never quite made it… and Why

A little spoken-about problem with writing fiction (and poetry) is writing too much and editing too little. Cutting often feels like a savage act of filicide. This is what this section of the site is all about: the work that didn’t beat the cut.

I screw up a lot when writing fiction. I overwrite because there’s no word count to adhere to. I introduce too many things. This means that I lose sight of the plot and subplots. Some characters end up being so much like other characters that there are no clear motivations for any of them (even I find them hard to discriminate between).

Therefore I benefit from editing by a third-party because that third-party is first and foremost a reader. A good editor will always make sure that the reader gets as much out of the writing as the self-indulgent fiction writer his or herself.

However, some things never get as far as an editor. I won’t let them out of the house. Some pieces of writing are so nearly bordering on ‘just right’, so close to ‘it’ that it takes a few out loud readings before I realise that instead of flying high, they just fall off a cliff.

Editing those slabs of text is not going to work. The editor is not a re-writer.

So, here’s an important lesson I’ve learned from 40 years of professional and personal writing: Adding more bits (characters, interactions, locations) rarely helps achieve clear plot and compelling characters. They can actually muddy the backbone plot, the main event.

Bad poetry (a side-eye view)

(When it comes to poetry, the same is true: too many adjectives, adverbs, similes, metaphors all combine to overgrow clarity. There’s little worse writing in the world than bad poetry – like a sharp clawed lion in the warm red glove of a fragile nightfall, it can take your face off or at least make you run from the savannah of poetry…. see?)

Back to the plot

You might have thought that decades of commercial writing for magazines, and book editing experience should have taught me to write more tautly. It should. It rarely does. Writing fiction, hard as it is for many of us who still love to do it, is deeply personal. This is irrespective of the genre or style of the work.

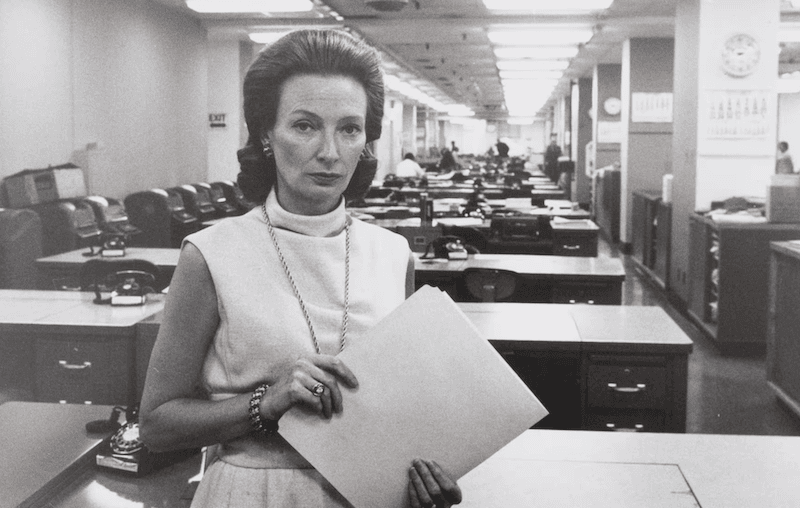

I started my training in the print world before moving online. Print is about tight discipline, strict rules, hard word counts and fixed deadlines. Print also has hardcore editors and subeditors who can sniff word bloat, fuzzy ‘facts’, informationally vacant quotes and so on. News editors are the best or worst depending on whether it’s your writing being eviscerated

The former is built on word counts, fitting to length, being organised within very tight structures. The latter has no print deadlines, no paper costs; it can be edited on the fly if needs be.

For example, a news story is an elegantly simply structured unit of communication:

Journalist and later editor of The New York Times, Charlotte Curtis in the New York Times newsroom.

Headline – grab the attention in a few seconds. It’s a competitive world out there. “President Kennedy Shot and Wounded in Dallas”

Standfirst/Strap – a little more flesh on the bones to drag those readers in. For example, “President’s life in the balance. Governor John Connolly also wounded. Mrs Kennedy in no danger. Public warned that the assassin or assassins remain the run”

Paragraph 1 – Your reader gets the basic story as signposted by the Headline and Strap. Par 1 is ‘What we know’. For example: “President John F Kennedy has been shot by a sniper or snipers today at 3pm in Dallas Texas. Doctors and surgeons are in attendance at Parkland Memorial Hospital. Your reporter is at Parkland awaiting news of the President’s life and death battle.

Paragraph 2 – More characters and locations can be added. For example, “Travelling with the 35th POTUS were… etc etc. Injuries to etc etc etc are not thought to be fatal.

Paragraph 4-6 – Comment from the people on the spot: crowd members, police, ambulance crews, surgeons, nurses, party officials, Mrs Kennedy if possible. Bobby Kennedy if possible. Lyndon Johnson of course, and either John Connally or one of his staff or relatives.

Paragraph 7-10 – We’ve got all the characters and all the locations, so now it’s time to speculate (expertly comment) a bit! The reason for this is that every other news outlet is running the same facts, so you need to retain attention and grow trust. For example: were any Cubans spotted in the area? Where was the Secret Service? Has the Secret Service made any comment? What does Dealey Plaza look like today? Who are the suspects? Where is the Vice President… and so on.

As you can see, the story is laid out cleanly and clearly in the headline. Your reader could stop reading there . They’d have the basic information to chew over in the local bar.

If they read on, other relevant characters and locations are added in strict order ensuring that the main story remains clear: In this case, the President has been shot and no one can say if he’s dead or alive. In theory a novel or short story (even a poem) could mimic the structure of a news story.

What you have is a structure (often called a Pyramid, with the point of the story at the top):

What happened?

Who did it happen to?

Why is it important?

Where did it happen?

When did it happen?

Why did it happen?

If only…

If only I could transfer my old news writing disciplines and structures to fiction, my life would be so much easier. But fiction writing is a very personal thing. Very personal indeed. So much so that it’s easy to fall into thinking that the reader is working not the other way around.

This is not to say that writing a journalistic piece is the same as writing a full-blown novel. From the get-go, the latter is dug out from your imagination. It’s up to you, the author, to make your characters, interactions, motivations, and all the locations and events believable, appealing and consistent. They can’t exist without you.